He was a cowboy, and like all cowboys, he did things hard. He walked hard, breathed hard, looked hard, bathed hard and licked hard. But more than anything, he loved hard. He loved so hard, in fact, that his late wife, Belinda, had expired three years ago from the seismic force of his love. Of course, the coroner had claimed her death had more to do with the bison that trampled her during the district’s 10th Annual Irregular Pottery Exhibition and Venison-Rubbing Competition, but the cowboy kept to his theory. He even brought in his own medical experts and held a town meeting to publicize their findings. But the townsfolk didn’t trust these experts, the fancy big-city outsiders who were too drunk to remember the script the cowboy’d written for them. In any case, he was available now, and the women in the valley eyed him like a piece of veal: they knew he was delicious but felt guilty for wanting him.

Illustrations by Skyler Luke Punnett

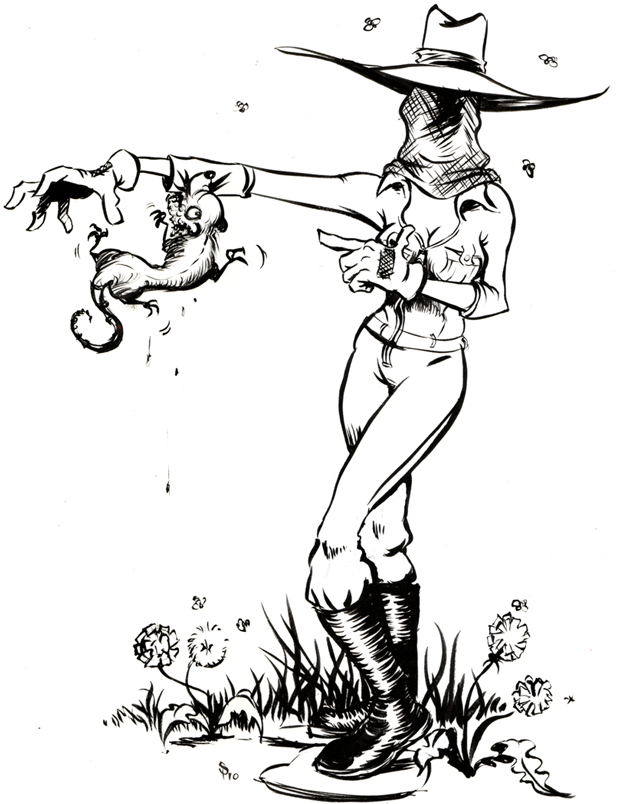

The cowboy felt the gazes of these women as he stalked through the town square at noon, zipping and unzipping the side pocket of his fanny pack. He paid no heed to their ravenous hunger, for there was only one woman whose affections he returned: Passion McPerry, a local widow who wore a beekeeping suit as a way of holding on to the memory of her late husband, who had perished in a bee-eating accident.

One day, as the cowboy sat on the porch of his ranch home, picking his teeth and wondering if there was such a thing as a store that sold stores to its customers, Passion McPerry sauntered over to his steps, swaying her hips and nearly falling over from heatstroke. She flashed him a provocative grin, or probably did, anyway.

“Hot day today, huh, cowboy?” she asked, eyeing his rugged, weather-beaten good looks and soulful, shimmering fanny pack.

The cowboy arched an eyebrow and cocked his imitation Thor helmet. “I reckon. That’s one of the funny things about heat. Everyone needs it, but nobody wants it. Like oxygen.”

Passion’s eyes welled. Probably not from the cowboy’s profundities, but because of the bear trap she’d stepped in earlier. “You know, cowboy, I’d never thought of it that way. Mainly because I usually don’t think about anything. Which is probably because I’m lacking oxygen.”

The cowboy said, “I’ve always figured thoughts were like broken legs: tipping over cattle is a lot more fun without both of ’em.”

The widow McPerry’s eyes glazed over. “And they can both hurt you if you push the wrong way.”

“True enough. Sister, here’s the one thing I think about the most: if we’re all just the tobacco in God’s big cigarette, how come we ain’t all been burned up yet? Follow-up question,” he added, “how come most of us don’t smell like smoke? There’s some womenfolk who smell like

flowers and springtime!” The cowboy wiped his brow, which was sweating like a sweat machine that can’t be turned off because its circuit board has shorted out from the tears of Old Clem, the guy who operated the sweat machine until he was replaced by a robot that would never join a sweatman’s union like poor Clem did.

After some time, Passion McPerry replied, “Don’t put much stock in God, I’m afraid. We been abandoned by him. Look at the horrible things in the world: the floods, the droughts, the killings. And this, too.” She raised her arm to reveal a rabid weasel dangling from it.

The cowboy shrugged. “Only one thing worth livin’ for in my opinion, sister. And that’s love.”

The widow beamed, and then reached out to touch the cowboy’s fearsome, bulging fanny pack.

Darren Springer is a graduate student in English at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.